Climate change is real, an indisputable fact that people across the globe have already experienced, given that extreme phenomena are now common, while their impact is greater.

|

Science and geophysical evidence not only point to this change, they stress it. In fact, the term climate change is no longer really pertinent, as this disruption in climatic patterns is already part of our lives and not some forecasted occurrence that might be avoided.

What we can do, what we are called to do, is to simultaneously alleviate or mitigate the impact of global warming to date and engage in concrete measures to contain any further heating of the atmosphere and the oceans.

This is all the more urgent as the impacts we are already experiencing result from an increase of roughly 1 degree above pre-industrial temperatures.

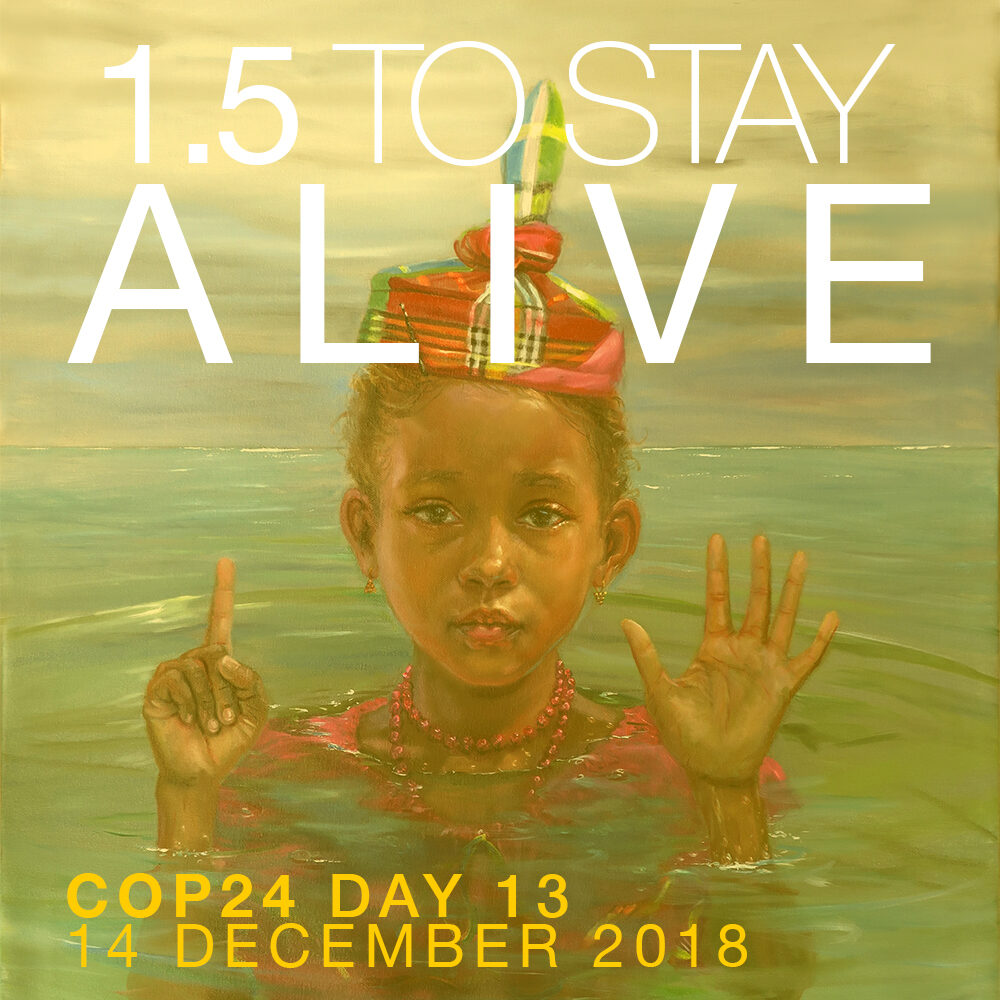

The 1.5° target is already a major concession

This means that the 1.5° target fixed by the Paris Agreement (2015) as a tentative optimal goal is already a major concession, for it entails significantly greater impacts, both in number and in severity, than now accepting as it does a further rise in temperature albeit limited to half a degree.

Hence, the 1.5° target does not mean an improvement on current conditions – it simply means containing the worsening of these conditions. But these will get worse, meaning that the impacts will be more devastating.

This is all the more certain as the 1.5° target refers to a planetary average, which masks regional disparities, whether in terms of differences in temperature levels or impacts due to the general warming.

In this context, the specific circumstances of small island developing states (SIDS) give rise to unique vulnerabilities, as evidenced in recent events and in the limitations they face in terms of response capacities, namely due to limited finances.

For us in the Caribbean, climate change signifies stronger hurricanes, more drought and resulting water shortages, a rise in sea level, heat waves, and warmer days and nights.

It is important to stress that, though the devastation wrought by hurricanes is more spectacular and hence more newsworthy, the impact of droughts is equally damaging in terms of food security, while an increase in heat waves and the number of hotter days and nights will affect – are already affecting – people’s health and wellbeing.

Small, poor and vulnerable nations and regions are those suffering the most

Climate change issues are issues of social justice

In fact, the adaptation to climate change must also address the question of climate justice, because there is a need for fairness and justice:

- on an international level, as small, poor and vulnerable nations and regions are those suffering the most from the impacts caused by richer nations’ development models

- locally, for it is the poor and vulnerable who suffer the most from the impact of climate change (e.g. fragile houses more easily destroyed by strong winds, small farm holders affected by drought and lacking access to irrigation, people with disabilities severely impacted when disasters strike, lower income households that typically do not have insurance, etc.). In other words, climate change issues are issues of social justice, which need to be taken into account in policy decisions.

Climate change issues are issues of social justice

Already, the 1.5° scenario requires us to adapt to, and (more urgently) envisage and prepare for, these more severe impacts. Concretely, it supposes that, in the policies we adopt to face up to climate change, we factor in a far hotter environment and the inevitable consequences it will have on our lives and on our habitat.

Current predictions are that the increase to 1.5° will happen sooner than expected, i.e. by the year 2031, so time is precious and policies need to be decisive. Furthermore, should this target be overshot for any reason, the scenarios for a temperature increase of 2° or 2.5° are exponentially worse than that of 1.5° – which would already be far worse than anything we know.

In the face of this challenge, the Caribbean must raise its voice to demand and support the respect of the 1.5° target. Indeed, advocacy, diplomacy and commitments must be both firm and ambitious, for it is necessary to ensure that the transition to renewable energy and a sharp reduction in emissions are not only implemented, but accelerated – for the sands are running out. This is a mission that should not be left only to climate change negotiators. Caribbean leaders and diplomats, the private sector and civil society must also be vocal on the international scene and at home.

Martin Luther King’s words in his fight against segregation sixty years ago ring just as true in our present confrontation with climate change: “The urgency of the hour calls for leaders of wise judgement and sound integrity – leaders not in love with money, but in love with justice; leaders not in love with publicity, but in love with humanity; leaders who can subject their particular egos to the greatness of the cause.”

It is up to each of us to become such a leader in our local civil society and, as citizens, demand of our diplomats and elected representatives to adhere to the same principles so that the Caribbean can be a leader in the cause of reining in our planet’s warming.

In this respect, we must grasp every opportunity offered to us to be in the vanguard of the battle to achieve the 1.5° target, adopting innovative solutions and showcasing examples proving that adverse situations can be overcome with tenacity – and for the good of all.

We need access to fundsto carry out infrastructure projects,pay for technological transfers

and educate our populations

As a region, we also need to rise to the adaptation challenges of this oncoming climate change as it will occur sooner, and not later, and even if we are not responsible for the main factors causing it. To do so, we need access to funds to carry out infrastructure projects, pay for technological transfers and educate our populations and we need to equip ourselves to be able to access that finance, while the institutions that manage global and regional funds must make it easier for those presenting viable adaptation projects to access funding.

At the same time, our adaptation and our response to climate change must not be reduced to a mechanical concept. It needs to be accompanied by a renewed approach of what we call economic development and by a change in mentality, so that it is included in the broader context of people’s livelihoods, social values and development priorities.